In light of the UK’s aim to be a ‘science superpower’ and ongoing discussions around the UK visa regime, Brunel Professor of accounting Peter Jelfs, and University of Essex's Angus Holford, and Tommaso Sartori examine the labour market contributions of UK and foreign-born PhD holders. They suggest that the UK could do more to explicitly attract STEMM PhD holders...

Every country wants to be the location of the next successful high-tech start-up. As it seeks to maintain its status as a ‘science superpower’, the UK is no different. However, there is a global war for talent, aiming to find and attract the founders of such companies. And sooner or later the reality is that these individuals, unless ‘home-grown’, will have to navigate the UK’s visa regime.

The visa regime is complex and subject to constant change, as seen in the recent adjustments to rules on minimum salaries for Skilled Worker visas, the ability to bring dependants, and the recent review of the graduate visa.

These changes have been touted as one reason for the 44% drop in overseas postgraduate student enrolments at UK universities between January 2023 and 2024. The US in particular actively targets foreign-born scientists to come for study and work. Other countries have attempted to compete using their tax systems to offer incentives. The UK, by contrast, offers a few minor benefits through its visa system to PhD holders, but is much less overt in its attempts to attract such individuals. And there is limited evidence as to what highly qualified scientists end up doing in the UK after arrival.

Our new research aimed to document the outcomes for the UK labour market of this system. We used 11 years of data from the UK Labour Force Survey, taking PhD-holders as a proxy for highly qualified individuals. We investigated their retention in STEMM (Science, Technology, Engineering, Mathematics and Medicine) sectors, their earnings, and propensity to set up a business. We made comparisons between foreign-born and UK-born PhDs, as well as between PhD holders and lower levels of qualification.

There were three key findings from our analysis.

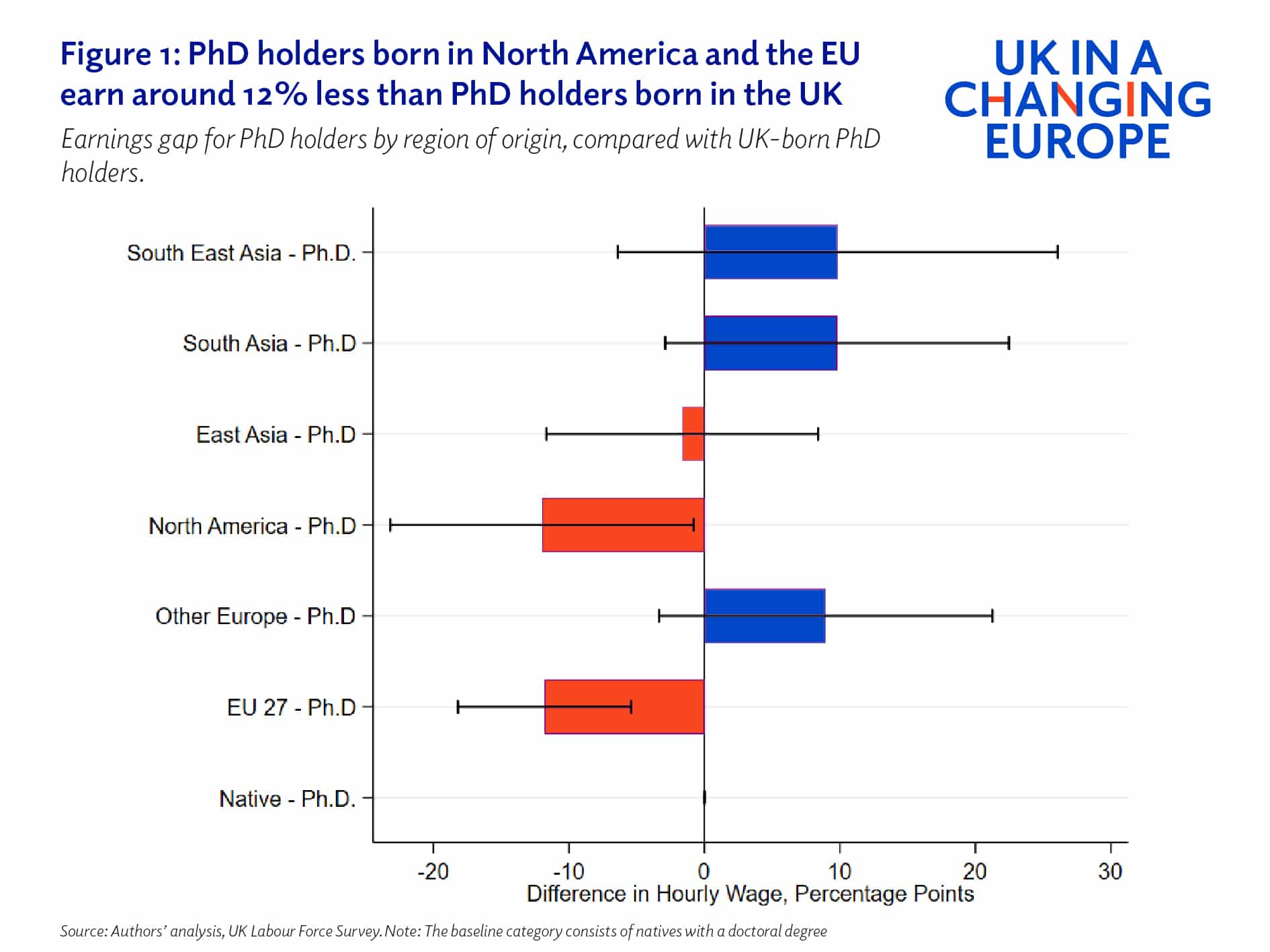

Firstly, PhD holders earn more than those with lower levels of qualification. However, PhD holders born in North America (who make up just 9% of foreign-born PhD-holders resident here) and the EU (31%) earn around 12% less than PhD holders born in the UK (Figure 1).

This result for North America-born PhD holders is likely to reflect the United States being much better at retaining its strongest PhD graduates than the UK. This is due to factors such as higher salaries and more attractive job opportunities, as well as a clear indication from national government that such individuals are seen as valuable assets. This means the UK is not well-placed to attract US-born PhD graduates from US universities to leave for the UK, or those from UK universities to stay rather than move back to the US.

And we suggest that this result for EU-born PhD holders reflects that, unlike those from all other regions, they enjoyed freedom of movement pre-Brexit, so did not need to meet salary requirements or the Resident Labour Market Test. This meant that the EU-born PhD holders resident here were perhaps on average less strong PhD graduates than those from other regions.

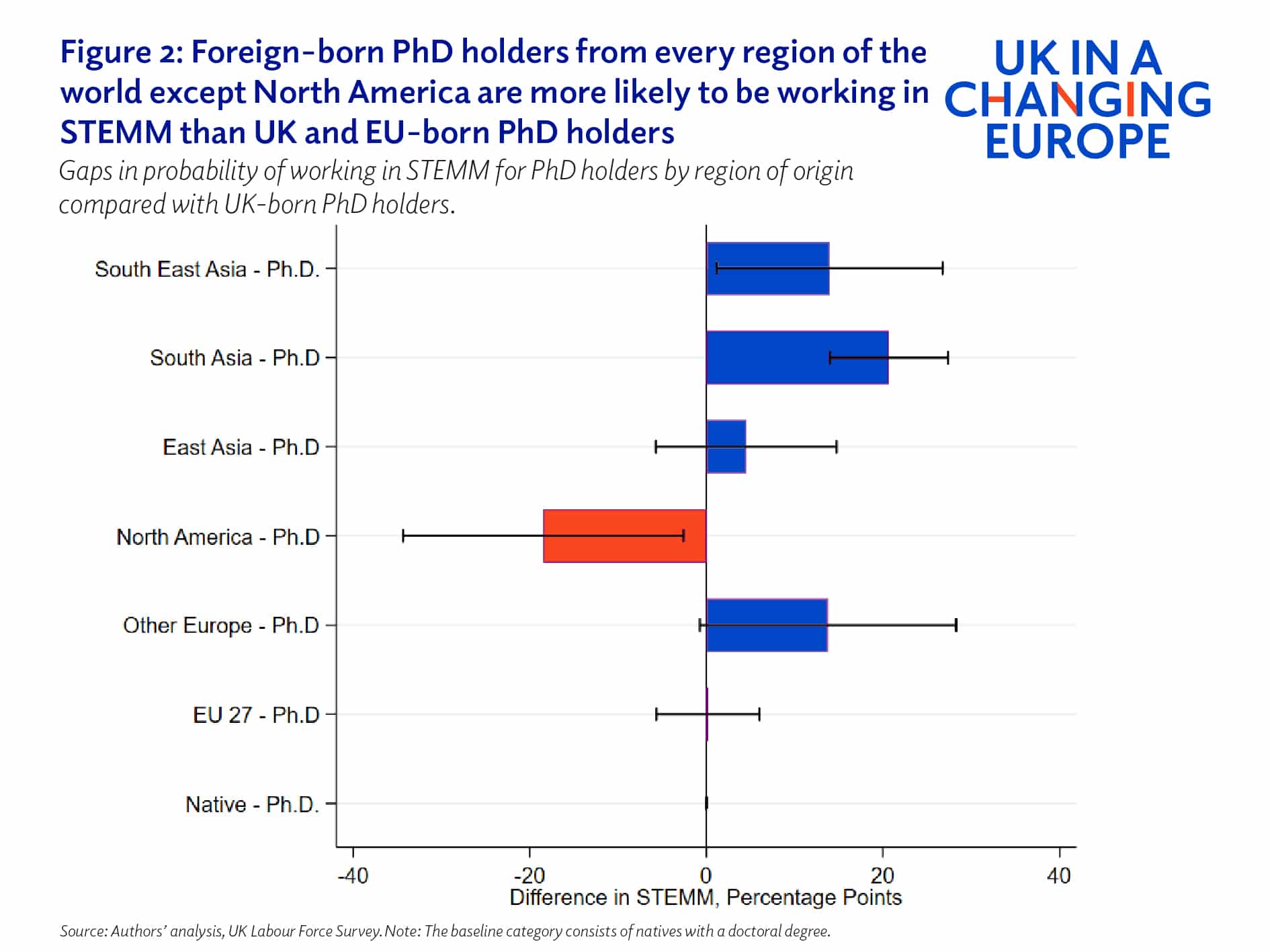

Secondly, PhD holders make up a disproportionate share of the UK’s STEMM workforce, with both native and immigrant PhD holders over 10 percentage points more likely to be working in STEMM than natives and immigrants with undergraduate degrees respectively. This link between PhD holders and the STEMM workforce suggests that it is reasonable for policymakers to target attracting PhD holders through visa or tax policy.

Foreign-born PhD holders from every region of the world except North America are more likely to be working in STEMM than UK and EU-born PhD holders. Those from South Asia are most STEMM-oriented at around 22 percentage points above the rate of UK natives, and North America born 18 percentage points below (Figure 2). Again, we believe this can be explained by the success of the US in retaining its most gifted scientists.

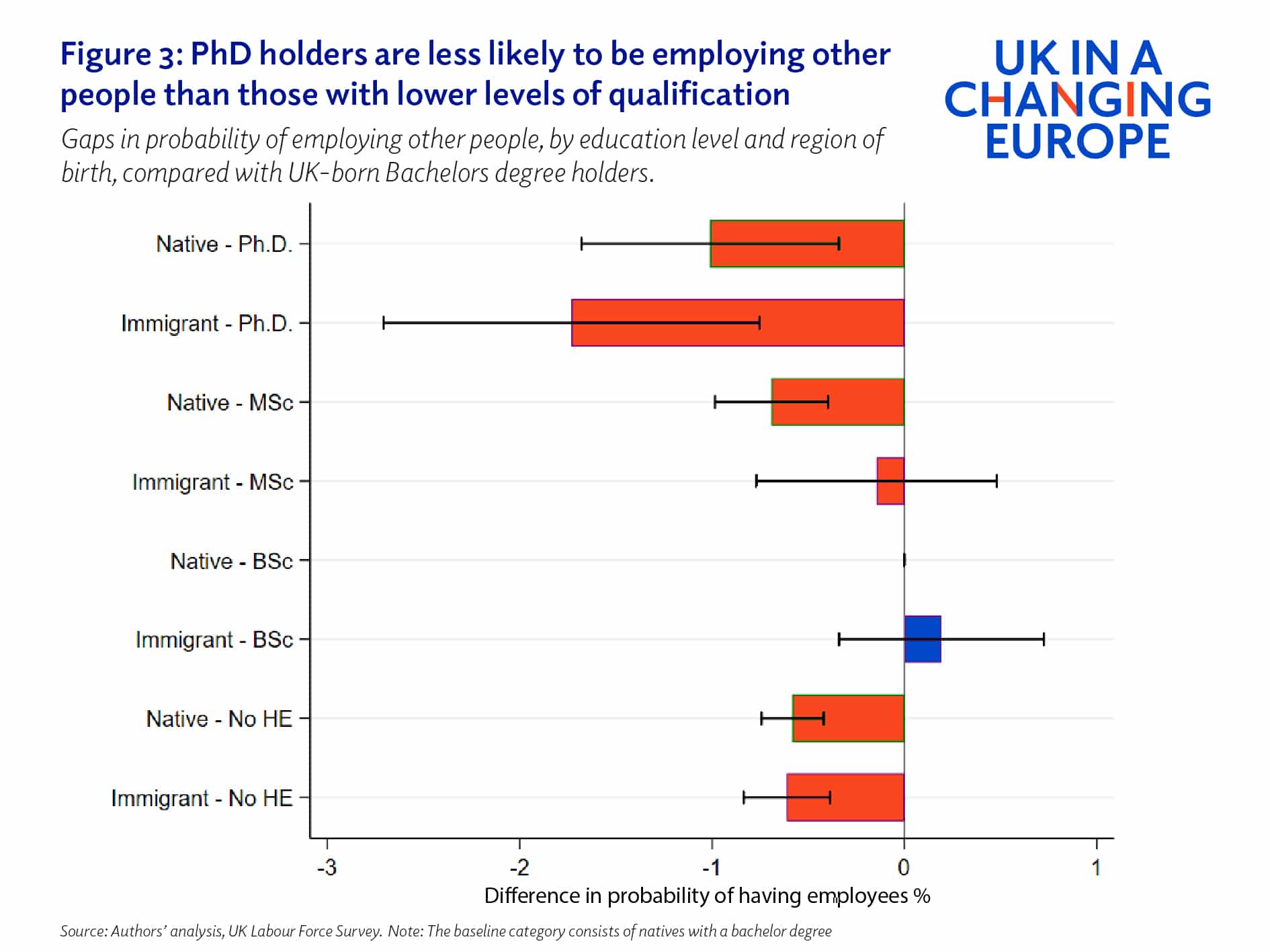

Thirdly, PhD holders are less likely to be employing other people than those with lower levels of qualification. In addition, foreign-born PhD holders perform less well in this area than native-born PhD holders, which is the opposite to the findings of US studies (Figure 3).

This may in part be due to the UK being seen as an unattractive place to set up an entrepreneurial business, but also because the current visa system makes it difficult. While some efforts have been made in this area, such as the introduction of the Innovator Founder visa, there are few applicants under this route and there is no explicit preference for STEMM businesses.

Post-Brexit, the UK has an opportunity to set its own coherent immigration policy. But frequent changes to the system and statements from politicians that fail to differentiate between different types of immigration do not help. Our research suggests that explicitly targeting STEMM PhD holders will be a beneficial policy change, and in line with the apparently successful approach of the US in attracting and retaining PhD holders.

As well as aiming to attract more STEMM PhD holders to the UK, a new visa route that specifically targets overseas STEMM PhD-holders who wish to set up a STEMM-related business in the UK could have a positive impact. This could be done by offering an attractive set of conditions, support from government, and a guaranteed minimum number of years to allow talented overseas individuals to plan their careers and gain certainty.

This article is republished with permission from UK in a Changing Europe https://ukandeu.ac.uk/about-us/about-overview/. Read the original.