Getting young children engaged in lessons at primary school can be a challenge. But using elements from video game culture in learning materials can make a big difference for both students and teachers, as shown in a new study by Brunel University London researchers and the media brand Checkpoint.

Video games have grown to be a significant part of mainstream culture, with Ofcom reporting that 9 out of 10 children play video games.

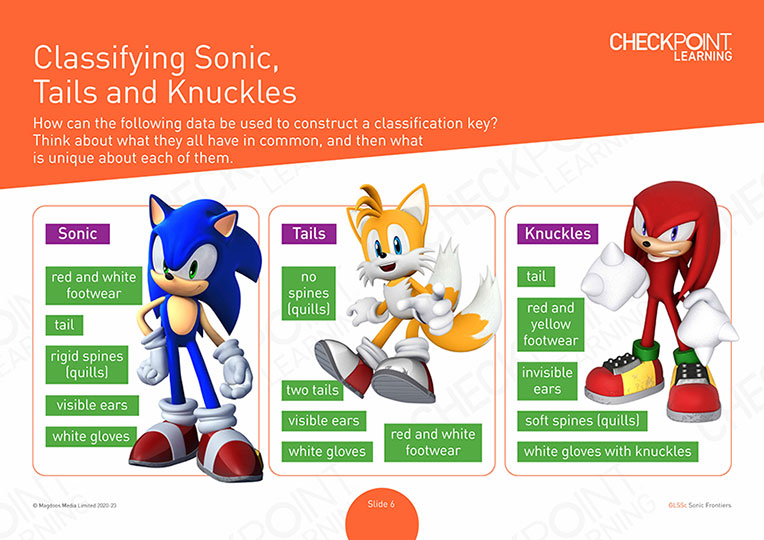

Checkpoint’s learning materials – ready to be used or adapted by teachers – tap into this gaming culture by incorporating it into primary education without direct use of games in the classroom, through use of well-known characters like Sonic The Hedgehog.

London-based Checkpoint started off as a gaming magazine but diversified into other gaming-related ventures, including their in-house-designed learning materials, which seemed to be welcomed by the schools they trialled them in. “But we wanted to see whether our approach actually had the benefits we intended,” said Checkpoint’s editor-in-chief Tamer Asfahani. “So we approached the educational experts at Brunel University London to design an independent study to evaluate the extent to which key stage 2 children engaged with our learning materials.”

Brunel’s Professor Kate Hoskins led a team of experts from the university’s Department of Education, who worked with five teachers at four London schools to trial learning materials for a science lesson that’s part of the National Curriculum. The aim of the lesson was for the students – aged 7 to 11 – to learn how animals are classified into different species and groups based on various characteristics, and to practice doing this themselves. Sonic and his fellow Sega characters were included to illustrate and emphasise learning points, utilising the students’ own gaming cultural wealth.

Through interviews and questionnaires, the researchers captured feedback from teachers and students, who were at schools in the diverse London Boroughs of Hillingdon and of Hammersmith and Fulham.

“The teachers were overwhelming positive about the key stage 2 science learning materials,” Prof Hoskins said. “They praised the engagement of children who at times struggle to follow a lesson. And the link to children’s game culture enabled participation across otherwise marginalised groups, including minority ethnic, SEND” – those with special educational needs and disabilities – “and low socioeconomic status children.”

One of the teachers pointed out how when they started talking about the character, the students were immediately engaged. “They loved the fact that it’s something that’s in everyday life. Especially the boys – they realise, okay, yes, that’s different,” the teacher said, adding that the learning materials were something that he and his colleagues can use as a basis, and adapt to the needs of various classrooms.

The students were similarly enthusiastic. More than 90% of the students agreed with the statement that the focus on video game content helped them to learn better. And when the researchers analysed which of the National Curriculum’s key skills were hit by the lesson, all the desired ones were being gained, with listening, creativity and problem-solving scoring particularly highly.

“The students’ responses suggest that incorporating gaming culture elements in the classroom can lead to a more enriching learning experience for students across the socioeconomic and cultural spectrum, transforming the way they engage with and understand scientific concepts,” Prof Hoskins said. “Teachers can potentially foster a deeper connection between students and the subject matter when bringing the excitement and challenges of video games into the learning process, ultimately promoting a lasting interest in science education.”

Checkpoint’s Asfahani welcomed the findings. “Thanks to this study, we have data confirming that teachers and researchers should work together to create innovative instructional strategies that harness the power of gaming culture and facilitate deeper learning for students, in key stage 2 science lessons and beyond,” he said.

“This collaborative effort will not only contribute to the ongoing development of effective teaching practices, but also inspire a new generation of students to become passionate, lifelong learners in the field of science and other subjects, especially for less confident learners.”

The research was made possible by the Brunel Innovation Voucher Scheme, designed to promote collaborative innovation between the university and UK-based small businesses, social enterprises and third-sector organisations.

The report – ‘Leveraging students’ game culture in education: Validating the benefits of utilising videogames to inform pedagogy’, by Professor Kate Hoskins, Professor Mike Watts and Dr Asma Lebbakhar from Brunel University London, and by Tamer Asfahani and Chris Winson-Longley of Checkpoint – is available to view. If you're still interested in delving deeper, then read the article.

Images © Magdoos Media Limited

Reported by:

Joe Buchanunn,

Media Relations

+44 (0)1895 268821

joe.buchanunn@brunel.ac.uk