■ With which organisations are people more willing to consent to the NHS sharing their health data or information?

■ How does anonymity (or lack of) affect people’s attitudes towards sharing their health data or information?

■ Does the use of the words ‘data’ vs ‘information’ make a significant difference in people’s attitudes towards sharing details about their health?

Before sharing our personal health data or information, there are often key considerations around context, benefits and privacy. New research from Brunel University of London has investigated the organisations that adults in England are most likely to consent to the NHS sharing their health records with and has surprising results about the attitudes towards sharing anonymised or non-anonymised data. The research reveals how the use of the words ‘data’ and ‘information’ can significantly affect people’s attitudes towards sharing their personal health details and provides implications for health-related organisations and companies.

The team of researchers, led by Prof Dorothy Yen, a marketing expert at Brunel, conducted an online survey of over 2000 adults in England with a mean age of 50. Participants were asked about the acceptability of the NHS sharing their health records with specific organisations, which included hospitals, GPs, social care providers, pharmacists, health insurance companies, pharmaceutical companies, and councils. The participants were asked if anonymity or a lack of it had any impact on their consent and whether the use of the words ‘data’ or ‘information’ impacted their decision to disclose details about their health.

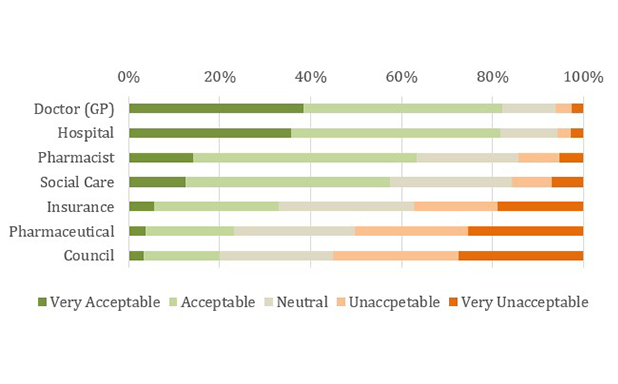

The results of this new study, published in the British Journal of Healthcare Management, indicate that people hold different attitudes on how acceptable it is for the NHS to share their data or information, depending on who it is being shared with. “Over 80% of participants perceived sharing their health data or information with hospitals and GPs to be acceptable or very acceptable, and this reduced to 63.4% for pharmacists and 57.5% for social care providers,” explained Prof Yen. “Acceptability was even lower for insurance companies (33.1%), pharmaceutical companies (23.2%) and city and county councils (19.9%).”

Figure 1. Overall acceptability of sharing data or information with different organisations.

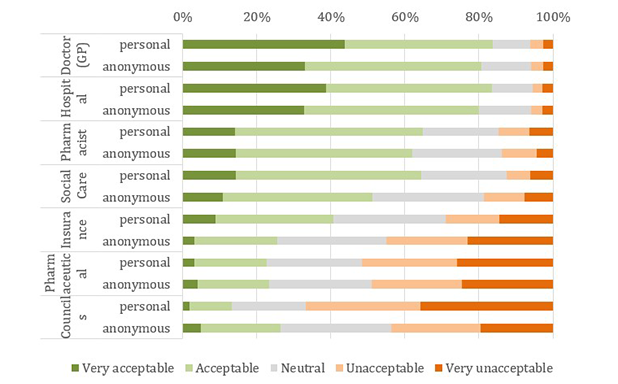

Participants found sharing personal (non-anonymised) data or information more acceptable than when it is anonymised when the organisation was a hospital, GP, social care provider or insurance company. “These findings challenge existing understandings about health record sharing, which often assume that it is more acceptable if the data or information is anonymised or given pseudonyms,” said Prof Yen. “It may be that participants could expect direct benefits from providing these organisations with personal and identifiable health data or information that is linked to them.”

In contrast, over half the participants found sharing non-anonymised health data or information with councils or pharmaceutical companies to be unacceptable or very unacceptable. “This may be because sharing with these organisations was not perceived to have any personal benefits,” explained Prof Yen. “However, participants were more likely to consider sharing anonymous health data or information with councils to be acceptable, suggesting that they recognise the purpose that anonymised data has in planning healthcare.”

Figure 2. Acceptability of sharing health records with different organisations where records were personal (non-anonymised) vs anonymised.

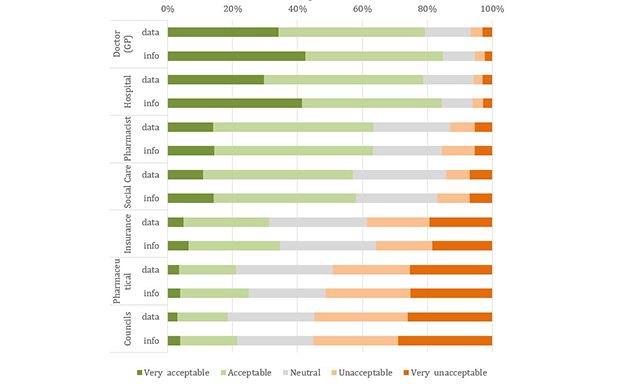

The words ‘data’ and ‘information’ are often used interchangeably to convey the same meaning, but when it comes to sharing details about our health, they may be perceived differently. “The terminology had a clear impact when the organisation was a hospital or GP, and participants were more likely to view sharing details with hospitals and GPs as acceptable or very acceptable when the term ‘information’ was used rather than the term ‘data’,” explained Prof Yen. “The difference between the two terms may indicate that the perception of benefits was prompted more strongly by the term ‘information’, which adds meaning and value to data and may influence decision-making from organisations.” Considering this finding, Prof Yen recommends that the NHS and other healthcare organisations consider using the word ‘information’ instead of ‘data’ in future communications when encouraging people to share their health records.

Figure 3. Acceptability of sharing health records with different organisations where the terms information vs data were used.

As a result of the study, Prof Yen highlights important implications regarding the sharing of health records across different organisations operating within Public Health England. “The results suggest that people evaluate the acceptability of sharing health records based on how doing so could increase the quality of the healthcare they expect to receive,” she said. “This supports the idea that the perception of direct personal benefits influences the acceptability of sharing health records, and making benefits clearer could encourage the public to allow their health information or data to be shared effectively and completely. When the direct and personal benefits are less clear, the public may be more reluctant to share their health records regardless of the terminology used or whether they are anonymised.”

‘Public attitudes towards disclosing personal and anonymous health-related data and information’, by Dorothy Yen, Han Dorussen, Steve Pickering, Martin Hansen, Thomas Scotto and Jason Reifler, is published in the British Journal of Healthcare Management.

Reported by:

Nadine Palmer,

Media Relations

+44 (0)1895 267090

nadine.palmer@brunel.ac.uk